How RRSP Contributions Reduce Your Taxes (With Real Canadian Examples)

Registered Retirement Savings Plans (RRSPs) are often described as a way to “save on taxes.” That statement is technically true—but incomplete. RRSP contributions don’t magically lower your tax bill by the amount you contribute, and they don’t benefit everyone equally.

What RRSPs actually do is reduce your taxable income. How valuable that reduction is depends on how much you earn, your marginal tax rate, and whether the money can stay invested long enough for the tax deferral to work in your favour.

This article explains how RRSP contributions reduce taxes in Canada, step by step, using realistic examples and plain language—no shortcuts, no blanket advice.

What an RRSP Contribution Actually Does

An RRSP contribution gives you a tax deduction, not a tax credit.

That distinction matters.

- A tax deduction reduces your taxable income.

- A tax credit reduces the tax you owe directly.

RRSPs fall into the first category. When you contribute to an RRSP, the amount you deduct is subtracted from your income before tax is calculated.

So if you earn $80,000 and contribute $10,000 to your RRSP, you are taxed as if you earned $70,000—not $80,000.

For the CRA’s formal definition and rules around RRSPs, see the official

Canada Revenue Agency RRSP overview:

https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/tax/individuals/topics/rrsps-related-plans/registered-retirement-savings-plan-rrsp.html

The tax savings come from paying tax at a lower income level, not from the contribution itself.

How the RRSP Tax Deduction Works (Mechanically)

Here’s the basic flow on a Canadian tax return:

- You earn income (employment, self-employment, etc.)

- Deductions are applied (including RRSP contributions)

- Your taxable income is calculated

- Federal and provincial tax rates are applied

The value of your RRSP deduction depends on your marginal tax rate—the rate applied to your last dollar of income.

A simple way to estimate RRSP tax savings is:

RRSP contribution × marginal tax rate ≈ tax reduction

This is an estimate, not an exact number, but it’s close enough for planning purposes.

Real Canadian Examples at Different Income Levels

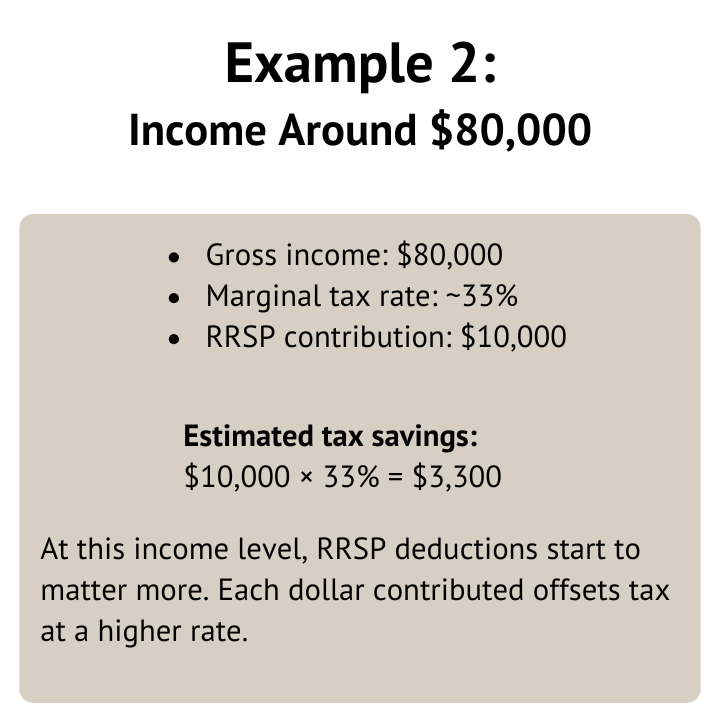

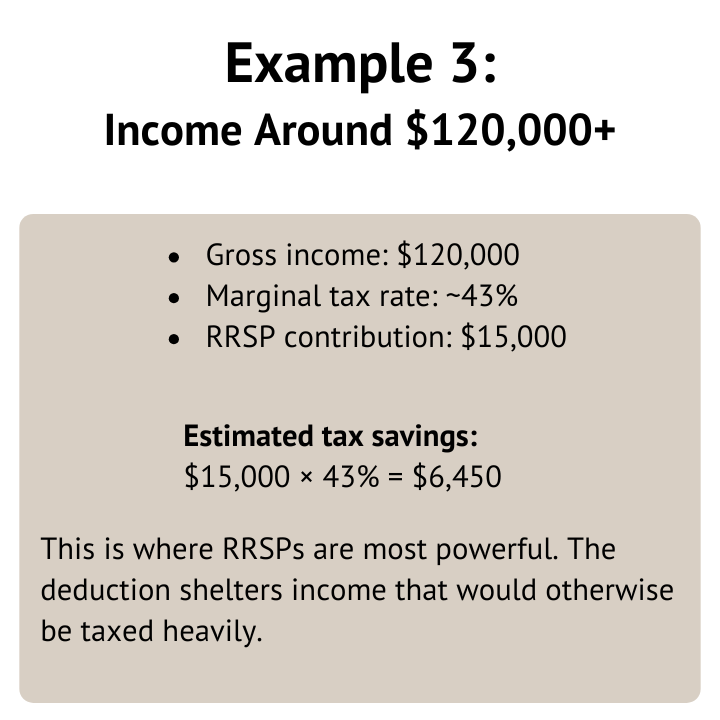

To see how this plays out in practice, let’s look at three simplified examples. These use approximate combined federal and provincial marginal tax rates. Exact results vary by province.

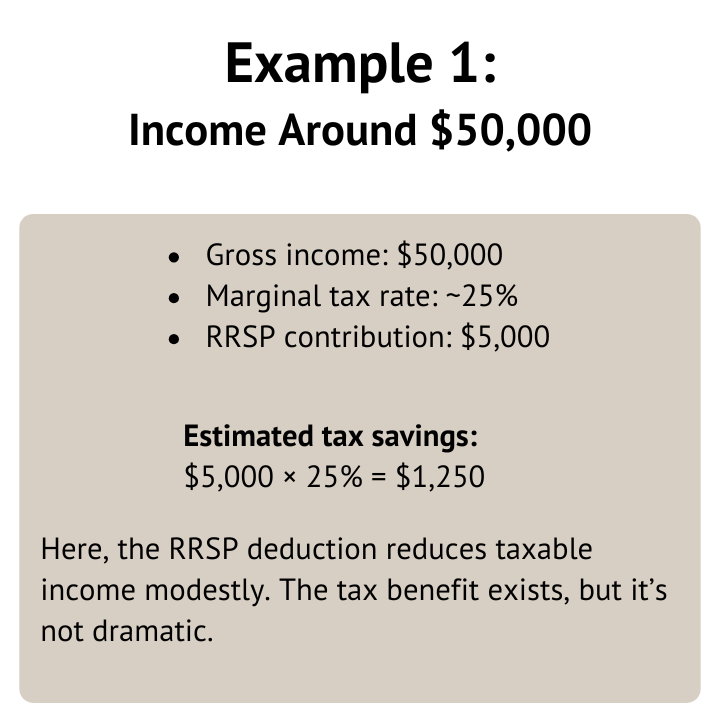

Example 1: Income Around $50,000

- Gross income: $50,000

- Marginal tax rate: ~25%

- RRSP contribution: $5,000

Estimated tax savings:

$5,000 × 25% = $1,250

Here, the RRSP deduction reduces taxable income modestly. The tax benefit exists, but it’s not dramatic.

Why the Savings Are Different

RRSPs are not “better” or “worse” investments depending on income—but the tax deduction is more valuable at higher marginal rates.

The higher your income:

- the higher your marginal tax rate,

- the more tax each RRSP dollar shields.

This is why blanket advice like “always max your RRSP” is misleading. The benefit is highly situational.

RRSP Refunds vs Actual Tax Savings

One of the most common misunderstandings about RRSPs is the tax refund.

A refund does not mean the government paid you extra money for contributing. It usually means too much tax was withheld during the year.

Here’s why:

- Employers withhold tax assuming no RRSP deduction

- When you claim one, you’ve already overpaid tax

- The refund is simply the difference returned to you

The real benefit of an RRSP is tax deferral, not the refund itself.

You’re delaying when tax is paid—ideally from a high-income year to a lower-income retirement year.

When RRSP Contributions Tend to Make Sense

RRSPs are generally most effective when:

- You’re in a higher tax bracket

- Your income is temporarily elevated (bonuses, commissions, overtime)

- You expect to be in a lower tax bracket later

- You have stable cash flow and don’t need the money soon

For many households, RRSPs work best after basic financial stability is in place.

When RRSP Contributions Tend to Make Sense

RRSPs are generally most effective when:

- You’re in a higher tax bracket

- Your income is temporarily elevated (bonuses, commissions, overtime)

- You expect to be in a lower tax bracket later

- You have stable cash flow and don’t need the money soon

For many households, RRSPs work best after basic financial stability is in place.

Who Should Consider Contributing Right Now

A quick reality check before contributing

If you have significant expenses coming up in the next 3–6 months—such as summer camps, vacation bookings, or sports registrations—contributing aggressively to an RRSP can create short-term cash stress, even if it lowers your tax bill.

RRSP deductions only help if the money can stay invested.

Contributing now and then, needing to pull funds back out later, often erodes the benefit through taxes, withholding, and lost flexibility.

Sometimes the most practical move is contributing less, not more—until near-term obligations are covered.

When RRSPs May Be a Lower Priority

RRSPs may be less effective—or at least not urgent—if:

- Your income is low enough that your marginal tax rate is minimal

- You don’t have an emergency fund

- You expect to need the money within a few years

- Government benefits and credits matter more than deductions

If you’re unsure what a reasonable emergency fund actually looks like, this breakdown may help:

Emergency Fund: How Much You Really Need (Canada)

In these cases, flexibility can be more valuable than tax deferral.

RRSP vs TFSA: A Timing Decision, Not a Moral One

At a high level:

- RRSP: tax break now, tax later

- TFSA: tax paid now, tax-free later

Neither is “better” in isolation. The right choice depends on:

- your current tax rate,

- your future tax expectations,

- and your need for access to the money.

For a deeper comparison of how RRSPs and TFSAs work in practice, see:

RRSP vs TFSA: Which should I max out?

https://growingwealth.ca/rrsp-vs-tfsa-canada/

For the CRA’s explanation of how TFSAs work, see:

Tax-free Savings Account (TFSA)

This isn’t about choosing sides. It’s about choosing timing.

Common RRSP Myths

“RRSPs permanently lower your tax bracket.”

They lower taxable income for the year—not forever.

“You should always contribute as much as possible.”

Only if cash flow allows and the money can stay invested.

“RRSP refunds are extra income.”

They’re usually just overpaid tax being returned.

“RRSPs always save more than TFSAs.”

Not true. It depends on tax rates now versus later.

How RRSPs Fit Into a Broader Family Finance Plan

RRSPs are a tool, not a starting line.

For most households, the sequence matters:

- Stable cash flow

- Emergency savings

- Debt strategy

- Long-term investing (RRSPs, TFSAs, etc.)

RRSPs tend to work best when they’re part of a broader financial system rather than a standalone decision. If you want to see how investing fits into an overall household structure, this overview may be useful:

https://growingwealth.ca/a-simple-family-finance-system-for-canadians/

If you’re unsure where RRSP contributions should actually be held (bank, brokerage, robo-advisor, etc.), see:

Where Should You Put Your RRSP? – coming soon

Tax efficiency only works when the underlying structure is solid.

The Right Question to Ask

The most useful RRSP question isn’t:

“How big will my refund be?”

It’s:

“What tax rate am I avoiding now—and what rate will I pay later?”

When you understand that trade-off, RRSP decisions become clearer, calmer, and far less stressful.

Affiliate Disclosure

💡 GrowingWealth.ca is supported by readers. Some of the links in this article are affiliate links, which means we may earn a small commission if you open an account or make a purchase — at no extra cost to you. We only recommend products and services we personally use, trust, or believe provide genuine value to Canadians. Our reviews and comparisons are always independent and objective.